At the start of the new academic year in Japan, early April, I joined a music circle and formed several bands with other members of the circle. During the summer break, one of my band’s members invited me to join his class’ study trip to Fukushima; gaining first hand experience at methods Fukushima’s civilians are employing to revitalize Fukushima’s tourist industry after the 2011 earthquake.

Brief history

The third largest prefecture in Japan, Fukushima is a northeastern region popular amongst Japanese not just as winter resort, but for its Japanese sake, food and many natural hot springs. Historically, Fukushima is known for it’s role in the last feudal Samurai war, the 1868 Bosshin War. Today however, the region remains heavily associated with the 2011 earthquake and subsequent nuclear disaster. An earthquake on 11 March 2011 led to a tsunami disabling most of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (located on the Pacific Ocean coastline of central Fukushima) and subsequent nuclear meltdowns due insufficient cooling. Despite strong criticism on government-level handling of the situation, much has been done on a local scale to restore Fukushima to its former level.

Itinerary

A system quite common to Japan and less so where I’m from is the zemi system (derived from the seminar system in Germany); classes of around 10 students working together with the professor in interactive ways about a specific topic the professor is interested in. Usually groups become quite tight and occasionally join the professor for some food and drinks at night, as well as go on study trips (read: glorified city-trips). Earlier this year I had the opportunity of joining my German professor and three other students from KU Leuven studying in Japan for such a study-trip in Matsumoto, but this was my first opportunity doing in a full Japanese context.

Although I was not part of the class, my friend and band-mate mentioned that that shouldn’t deter me from joining; in fact due the topic in question, input from a non-Japanese student would actually be highly appreciated, or so he assured me. Taught by Dr. Prof. Hosono (細野教授), the class itself (FLP, or Faculty-Linkage Program) is open for students of different academic backgrounds and often focuses on international issues. This semester, students worked on city-planning in disaster-struck areas (まちづくり) with a case-study of tourism in Fukushima.

The students worked around the concept of a Fukushima Hope tour (福島県HOPETOUR). How can Fukushima citizens work bottom-up towards reigniting Fukushima tourism? How should they utilize technology such as social media and translation tools to draw in foreign tourists; how can they shift the focus point from so-called disaster (dark) tourism? Are there any routes throughout Fukushima offering starting points to Fukushima’s history, cuisine and natural beauty? What strategies are appropriate to attract previous tourists in different seasons?

The three-day itinerary planned around Fukushima would first visit the formerly abandoned villages of Namie (浪江) and Tomioka (富岡町), passing closely to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant itself. During this time, students have the opportunity to talk to some of the locals who’ve decided to return there and reopen businesses. Afterwards, the bus will head for a japanese-style inn (旅館) at Iizaka Hot Springs, near the centrum of Fukushima, were we will spend the night. The next two days were spent in the Aizu (会津) area, specifically Aizu-Wakamatsu (会津若松), Kitakata (喜多) and Ouchijuku, focusing more on the historical aspects of Fukushima as well as natural beauty and cuisine.

HOWEVER! I just purchased a new smart-phone several days earlier and I found out the hard way my alarm app did not function properly. I woke up two hours too late and missed my train to Tomioka. I was forced to buy a new bullet train ticket and catch up with the group in Iizaka, missing the first part of the itinerary. (ू˃︿˂ ू)

Fukushima City

After a brief mental breakdown over oversleeping and missing my train, I ended up going directly to Fukushima City by bullet train and spent a few hours walking around the city, having a brief conversation with an old baker who’d never talked to a foreigner before and was interested in my opinion on the texture of his melon pan (decent). After a further uneventful trip I headed towards Iizaka through the cute Iizaka Line (飯坂線) and met up with the FLP class who’d arrived around the same. Not the best first impression but it didn’t really bother anyone.

iizaka onsen

Iizaka Onsen (飯坂温泉) is a quaint hot springs resort in the central area of the Fukushima prefecture (Nakadori, 中通り). Coming straight from Tokyo, the town does have a bit of a rustic look, somewhat shabby even at times, but that’s part of the charm for sure. The town is historically based around its natural hot springs and there are many public baths, traditional Japanese inns, as well as free foot-baths around.

Although we ended up using the hot springs at our inn, we passed the oldest public baths in Japan, Sabakoyu (鯖湖湯), famous for having been visited by famous poet Matsuo Basho and reaching temperatures up to 50°C. These public baths form a social function and even now the free foot-baths around are used by weary passengers taking a break and having a chat.

The inn we stayed at, Horieya inn (ほりえや旅館), was established in the 1815 and is still run by the same family. While a bit modernized to accommodate modern necessities, The wooden architecture and base of the building has remained completely intact. Before dinner, one of the proprietors briefed us on Horieya Inn, Iizaka Onsen, and the methods Iizaka locals are employing to revitalize tourism in the area. Everything is done on a community-scale, including digital techniques such as home-pages and social networks as Twitter. Even the website (linked above) is made in-house, and while very much bare-bones, displays the tenacity and perseverance of a mostly aging community to utilize new technology, as well as a lovely sense of humor. Do note the English, Chinese and Korean accommodation of the website using Google Translate.

On that topic, it is worth checking out the official Iizaka Onsen’s website as well. Despite similar design choices, the tourist association has taken much care in providing handmade translations in English, both traditional and simplified Chinese, Korean, Thai and Russian, as well as providing maps throughout the town highlighting natural beauty and cuisine throughout the four seasons. Bicycles and umbrella’s are available for free at the station, by the way.

Our meal, made with fresh community-driven Iizaka ingredients was delightful, as was the Onsen and our room (I stayed in a room with another graduate student and my band-mate, nicknamed 赤パンツ or ‘red pants’ for his daily choice of trousers, by the way). At night, we joined several other students for some drinks and a few rounds of party-game Werewolf (jinro, 人狼 in Japanese). Tips for future players, abusing your status as Japanese-learning foreigner is an easy way to feint innocence. One of the fourth year students, responsible for some of the trip’s organization and financial aspects, found out about gathering and got rather angry that we weren’t sleeping yet, going so far as to insinuate we were irresponsible. A bit of a mood-killer, we returned to our rooms and slept briefly but well.

Aizu-Wakamatsu

Our next day was spent around the castle town of Aizu-Wakamatsu (会津若松), as well as the nearby Ouchijuku (大内宿) and Iimoriyama (飯盛山). Historically, Aizu-Wakamatsu is known as a castle town of the Aizu Domain and the main setting of the Boshin War, a civil war between those in support of maintaining the shogunate system (the feudal Japanese military government), and those trying to overthrow the shogunate after discontent regarding Japan’s opening to the west.

While 2018 marks 150 years since the Meiji Revolution, the Aizu region aims to focus rather on 150 years since the Bosshin War, hoping to attract tourists for its samurai history. We headed to Aizu Bukeyashiki (会津武家屋敷), known as a residence or mansion for high ranking Aizu samurai. The building is quite extensive and attempts to sketch daily life of Aizu samurai in the middle ages. During our talk with one of the proprietors, we learned of the Aizu-Wakamatsu community to in similar fashion utilize technology to attract and re-attract both national and international tourists; teaching staff how to use voice-translation software and implementing credit-card payment systems around town. The following Youtube video attempts to portray the natural beauty of Bukeyashiki during all four seasons.

We stayed in a hostel near Nanokamachi Street (七日町通り), close to the famous Tsuruga Castle. While the current one is a concrete replica, the original castle ( was demolished after the Boshin war) served as administrative center of Aizu and has ties to the famous Date Masamune. The inside of the building has been rebuilt as museum with some interactive elements and various video-material displaying the history of the castle and Aizu samurai. The view from the top is worth the entrance.

Iimoriyama

Iimoriyama (Mount Iimori, 飯盛山) is a hill most famous for a famous media event related to the Bosshin War. The story tells the tragic suicide of a group of 19 teenagers (belonging to the Byakkotai 白虎隊 or White Tiger Company military unit) who had retreated here to assess the situation, and (wrongfully) believing the castle had fallen, committed ritual suicide as final means to defend their honor. This story is one of many tragic so-called bushido-related stories immortalized as war-time propaganda, and actually impressed Italian fascist leader Mussolini to the extent he donated a Pompeii archaeological column to the site. A 1930’s donation from German side can be found here as well, in the form of a black granite plate with an Iron Cross inscription.

Another interesting construction is the Aizu Sazaedo (会津さざえ堂), a completely wooden hexagonal Buddhist pagoda built in 1796, known for its ‘double-helix’ structure. The building is devoted to Kannon, and worshipers descent the building through a different way as the ascent to avoid disturbing each other. Aside from the striking wooden construction, visitors will immediately notice an enormous amount of labels with calligraphy attached pretty much everywhere. This was done by Edo period ‘tourists’ as proof of one’s visit. Some things never change.

Honestly, the lush nature juxtaposed with the plentiful faded gravestones, the wooden Aizu Sazaedo and the oddly befitting Pompeii eagle make Iimori an absolutely beautiful, must-visit area when in Fukushima.

Ouchijuku

Our next visit was the former post town of Ouchijuku (大内宿), which connected Aizu with Nikko during a period in which restrictions by the shogunate let by frequent obligatory travels to the capital of Edo (modern-day Tokyo). The area has been redeveloped as popular tourist destination for those looking for an authentic view of Japan’s feudal history. The region thrives on tourism, with many shops selling handmade trinkets or grilled fish. One of the proprietors of a tatami-floored restaurant we had dinner took some time to explain some processes of their local cuisine (negi soba, scallion buckwheat noodles)

The well preserved buildings, with thatched roofs made from dried straw, dirt tracks, and untouched natural beauty (electricity cables are buried underground) have made this place a highlight of my stay in Japan. We spent the remainder of our day around this area before taking our bus back to our hostel.

Before dinner, professor Hosono held an impromptu class on the topic of city planning, and asked the students to present their findings. As a foreign student, I was asked of my experience as well and had to present some ideas on revitalizing tourism in Fukushima, drawing attention away from the 2011 earthquake and disaster tourism. After dinner, I joined most of the students for a final drink (お疲れ会) and some games before calling it a day.

Kitakata

The next morning, we visited Kitakata (喜多), a city in Aizu today known particularly for its many ramen restaurants (over 130 stores!), sake and historic warehouses (kura, 蔵) used for storing dried foodstuffs. It’s commonly said that the high quality water in the neighborhood lead to its famous production of sake and noodles, but before we could try this ourselves we were led to a completely different shop: the Okuya Peanut Factory Shop.

Apparently, Kitakata is rich in peanuts. We had an interview with the proprietor and received a tour around the stock-house, detailing both the business’ history as well as the technical aspects of processing peanuts. The things I’m learning on exchange in Japan. Okuya Peanut Factory Shop has grown to the point this originally one-man-business is now a strong exporter of both refined and unrefined peanuts and became a local hot-spot for peanut soft-serve ice cream.

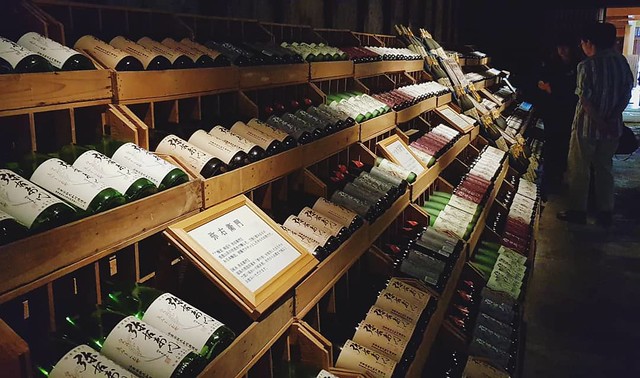

Peanut Ice Due the clear, high quality waters nearby, the town of kitakata has plenty of premium sake breweries as well. We visited the Yamatogawa Sake Brewery, dating back to 1790 and using only in-house cultivated Kitakata water and rice. We had the opportunity to visit their storehouse and engage in some tasting.

After our sake tasting, we had just an hour for lunch before ending our study-trip, and hurried to arguably the most famous ramen restaurant in Kitakata: Abe Shokudo (あべ食堂). On our way, we actually passed a small shrine dedicated to ramen. No time for distractions though; there was some serious eating to be done.

That’s right. Two pictures. My band-mate is a known ramen-aficionado and we ended up using our limited time during lunch to visit a second ramen restaurant right after, Makoto Shokudo (まこと食堂). Although we were several minutes late to our bus back to the station and thus again got scolded by the fourth year student in charge of organization, I can’t say I regret making the decision to have a second portion.

Conclusion

I’m still a bitter I missed the first part of the trip, but nevertheless it was a wonderful experience joining my friend on a school-trip and something I hadn’t expected to happen while studying in Japan. A good combination of studying, tourism and playtime amongst other students, I didn’t get too much sleep this trip but instead I got first-hand experience in Japanese student-life and good memories. Many talks with local citizens collaborating in revitalizing Fukushima’s tourism helped me get a deeper insight into aspects of marketing as well as the great extents of community-driven development.

The prefecture of Fukushima is in the public mind still, and especially amongst foreign tourists, deeply connected to the 2011 earthquake and nuclear disaster; needless to say dramatically affecting Fukushima tourism. Regardless of my opinion on nuclear energy and the handling of the actual incident, international research does show radiation levels on average in Fukushima, especially in distant areas like Aizu, to be equal or even lower than the average of unaffected major cities around the world. While tourists are primarily drawn to regions as Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto and Nara; there is much to be discovered in Fukushima, a region of exceptional natural beauty, local cuisine, hot spring baths and well-maintained historical elements in daily life scenery. I thus sincerely do recommend future travelers to travel outside of this fixed ‘Japan-itinerary’ and enjoy the lifelong efforts of local communities such as those of Fukushima to promote their homes to travelers.

Gallery

-

Ouchijuku by Stevie Poppe (https://flic.kr/p/2euNnmK - CC BY-SA 2.0) ↩